COLUMN: Exhausted after a Zoom meeting?

Navigating through a new set of social norms and protocols from virtual communications can be taxing

Ashlee Dauphinais is a graduate student in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese studying Hispanic Linguistics. She was among 18 graduate students recently awarded an autumn 2019 Presidential Fellowship, the most prestigious award given by the Graduate School at Ohio State, as well as a recipient of a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad fellowship given by the U.S. Department of Education for twelve months of research in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil during 2018-2020. The Center for Languages, Literatures and Cultures asked her to write a column about the digital exhaustion that comes after communicating via Zoom.

Before this semester, I had never used or even heard of Zoom.

“Zoom University,” as some have started to dub it, has now become a way for us to do the things we want and need to do and stay healthy while doing so. Since Ohio State moved to virtual classes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, I have used the application to attend and conduct classes, to carry out oral exams with my Spanish 1103 students, to host office hours, to give guest lectures at other academic institutions, and to sit through work and research meetings of varying sizes and lengths. I have witnessed fellow graduate students’ virtual dissertation defenses and MA paper presentations. Beyond the university setting, my 200-hour yoga teacher training and dance classes have been transferred to Zoom, I have organized calls for family members, and my friends near and far have invited me for virtual dinners and hangouts.

Did that sound like a lot? Because it sure has felt like it to me!

If you’ve ever been immersed in a new cultural or linguistic setting, such as study abroad, you might recognize the mental fog that sets in after a day or two of beginning to operate in this environment and using the target language.

Our brains are working extra hard, and researchers have even found that our brains consume even more energy (aka calories and glucose!) while undertaking more intensive and taxing cognitive tasks. Although at first glance it might not appear to be so different, linguistics and anthropology can tell us why there is good reason for us to be exhausted after interacting on Zoom or other video platforms, besides the most obvious ones such as exposure to blue light, more sedentary behaviors, and interruptions to sleep.

Language is not just the stream of acoustic vibrations in the air emitted from vocal cords that get picked up by our ears. Anyone who has had a confusion or misunderstanding from not picking up on tone or intonation via email or text message understands this pretty well.

As a whole, language involves a complex and embodied system of meaning that involves almost every muscle of our body. It requires a complex choreography of even the most minute gestures, facial expressions, eye movements, context, and even physical presence and touch to create rich and meaningful communication that by a certain age become pretty natural.

Despite this, our ability to decipher gestures and facial expressions in this new virtual environment is significantly decreased, often exhaustingly so, with communication taking place over a dimly lit and highly pixelated screen that freezes and snaps on the regular.

Even in the most ideal of technological settings, we have to put in a lot more effort and expend more energy to be communicative. There are many ways that the end of a speaking turn become less apparent when communicating online, and it is a lot easier for multiple individuals to speak over each other at once as our sensation of what is an acceptable pause or silence is altered.

The chance for mishearing certain sounds due to differences in what frequencies naturally get filtered out over microphones and computers is also equally high. For those who live alone, almost all of the communication you have with other people might very well be almost exclusively via digital or virtual means meaning that even the most enjoyable interactions such as chatting with your closest friends may quickly turn into a chore.

From an anthropological perspective, we are simultaneously adjusting to a new set of social norms and protocols, outside of the obvious ones. What is deemed appropriate etiquette in this almost exclusively virtual world? We are learning things such as how to tell when it’s necessary to mute yourself, or when it’s considered unacceptable to have your camera on.

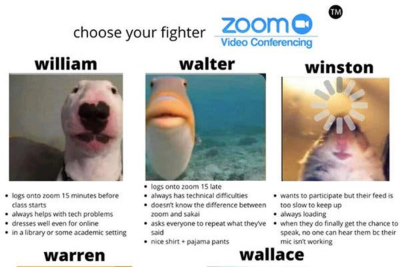

You might find yourself asking, what does your virtual Zoom background say about you? How professional of an attire am I required to wear, and is it rude to check that email while in this meeting? How do you deal with “arriving late” to a meeting, and what is the appropriate protocol if I have to leave? Memes, such as the one on the left, demonstrate the complex social acrobatics we do as humans to organize our world. Pets, children, and roommates may now find themselves wandering into the most professional of meetings in a bizarre remix of all facets of our life that have merged into one platform. We are in the middle of doing the extra work to learn how to navigate these new settings.

Under “normal” circumstances, physical spaces provide us for context and a place for conducting certain work that might not be available to us at home, and we are generally comfortable operating in them and are aware of the norms for communication and behavior. They additionally provide a division of our attention and energy to allow us to shift our focus to different areas of our life that need our attention.

Social sciences like linguistics and anthropology show that we are very adaptable to new circumstances, but that doesn’t mean that it will always be easy especially in the beginning. Depending on the nature of your work, there may be less options for avoiding this digital exhaustion. However, being aware of what is going on will hopefully help to not feel like this is only happening to you. I believe that exercising the values of empathy, patience, and understanding with others and ourselves as we attempt to make sense of these new social and linguistic norms is one of the best things we can do. It is equally important to reflect on how to establish boundaries in the different spaces of our new digital lives the best we can, while making sure we’re staying healthy, hydrated, and rested the best we can.