The Return of Yiddish

The Yiddish revolution at Ohio State is coming.

Starting this fall, students can enroll in Yiddish language classes for the first time in more than a decade. The Yiddish and Ashkenazic Studies program has its first student declaring a minor in eight years. A Yiddish culture and language club debuted two months ago to help Yiddish students practice their speaking skills and dive into the culture.

Since joining Ohio State as the director of Yiddish and Ashkenazic Studies last semester, Sonia Gollance has re-energized Yiddish at the university, developing a minor program that explores the complexities of the culture with new literature and language courses and building a community of Yiddish learners within the campus and beyond.

This isn't a Yiddish revival. It’s a Yiddish rebirth.

“I’m excited about having students coming in who don’t know what they are about to learn having their minds blown,” said Gollance, a visiting professor in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures.

The department has offered Yiddish language, literature and culture classes since 1978. In the ’80s and ’90s, Ohio State was home to a thriving Yiddish program. Two Yiddish Studies professors taught language, literature and culture courses, which “made it one of the largest Yiddish programs in the hemisphere,” Gollance said.

But over the past decade, following a retirement, the Yiddish program has only offered general education classes.

“Languages are meant to be spoken, and it’s really exciting that that will be happening here again,” Gollance said. “But it makes sense too: Ohio State has really strong German and Jewish Studies programs, and schools that are strong in those fields often offer Yiddish as well.”

Department Chair Robert Holub said strengthening the Yiddish program has been a top priority for the past two years.

“We need to have a vibrant program in Yiddish language, which is closely related to German, and we need to emphasize the many connections between German and Yiddish culture, and the significance of the problematic German-Jewish symbiosis for understanding the past two centuries,” said Holub, who is also a professor in the department. “Yiddish plays a central role in fostering this understanding. We are delighted that (Gollance) has made such tremendous progress in such a short period of time, and we welcome and support the Yiddish revolution she has started.”

The Yiddish minor includes three Yiddish language courses and five culture and literature classes. The first of the language courses, Yiddish 1101, will be offered in the fall.

You don’t have to have a family connection to study Yiddish, said Gollance, whose work focuses on literature, dance, theater and gender studies.

By studying Yiddish, students can get a better understanding of a wide range of topics such as Eastern European history, Germanic linguistics, Jewish genealogy, religious thought, radical political movements and debates about immigration and American identity.

Through Yiddish literature, students can engage with powerful texts that have often not been translated into English. By studying Yiddish culture, students can learn how Ashkenazic Jews express their spirituality and celebrate life through song and dance.

During Gollance’s Yiddish Culture class last semester, students learned about “broygez tants,” a wedding dance in which mothers-in-law would pantomime fighting and making up. She showed students how to perform the dance in class, working with them to express anger (or cope with midterms) through gestures and stomping.

Yiddish has a linguistic diversity that students may find interesting, she said. It is a Germanic-based language with elements taken from Hebrew and Aramaic as well as from Slavic languages and traces of Romance languages.

Prior to the Holocaust, there were more than 11 million speakers of Yiddish; 85% of Jews who died in the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers. Today, there are less than a million Yiddish speakers worldwide, living in cities such as New York, Paris, London, Antwerp, Jerusalem, Montreal, Buenos Aires, St. Petersburg, and Melbourne.

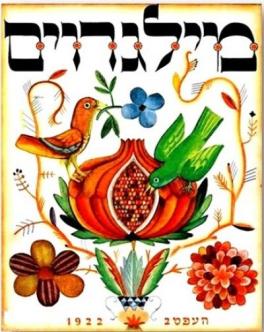

The Yiddish minor includes three Yiddish language courses and five culture and literature classes. The first of the language courses, Yiddish 1101, will be offered in the fall. It will feature a new textbook that only a handful of universities are using. Gollance said the new textbook is a game-changer as it implements the latest thinking about how people learn languages and integrates cultural content. The class will also include a variety of cultural materials including Yiddish folk songs.

Kerica Bucks is the first student declaring a minor in Yiddish in eight years. As a history major focusing on modern American social and cultural history, she said Yiddish can enrich her historical research.

"To hear that I would get to be a part of the program's rebirth was exciting," she said. "I felt lucky, but also surprised. It was surprising to find out that Ohio State has a Yiddish program and even more surprising to hear that it's being brought back right as I start college."

She wants to become fluent in Yiddish and eventually work with historical documents in Yiddish created in the United States.

“They say Yiddish is the language of many revivals,” said Casey Washer ’11, who launched Yiddish Tisch, a monthly Yiddish culture and language club at the Schottenstein Chabad House at Ohio State. “It’s had more than one comeback. It was really decimated during the Holocaust, and then the people who were really speaking it were in Hasidic communities. So, it’s kind of cool to see people taking an interest in it now.”

The club, which meets every last Tuesday of the month at the Chabad House, offers a social setting for students to learn and practice Yiddish. Washer said Gollance serves as the club’s “scholar in residence,” providing support and materials for the meetings.

Meanwhile, Gollance has been working to raise awareness about Yiddish at the university, connecting with campus and community Jewish organizations. She gave a presentation at the new student-run Polyglot Club, which promotes all languages at Ohio State; taught adult education sessions with the Melton Center's Advanced Text Study Group; and led a Yiddish dance workshop for the cast of the Department of Theatre’s production of “Indecent,” a play about a scandalous Yiddish play that ran through Thursday.

After less than a year at Ohio State, Gollance is only getting started.

She has been approached about working with Columbus Jewish Community Center and is looking to develop partnerships with Ohio State Hillel, the hub for Jewish life and experiences at the university, as well as with dance and theatre programs.

She hopes to develop some new literature and culture classes that would appeal to students in a variety of majors such as a class on trains in Yiddish literature.

“Trains are often a symbol of modernity,” she said. “They’re a place for strangers to meet and talk to people they’ll never see again. But trains could also bring anti-Semites to carry out pogroms against Jews, and trains were used during the Holocaust to transport people to death camps. It would be really interesting to talk about all of these different layers of meaning and how we think about technology in literature.”

She wants to incorporate real-world assignments to raise the profile of Yiddish figures. For instance, students in her Yiddish Literature in Translation class are writing blog posts for possible publication on a Yiddish theatre blog.

“A lot of Yiddish literary figures aren’t well known by the general public, and I could see another class having a final assignment where we research and write Wikipedia entries about underrepresented Yiddish cultural figures,” she said.

Gollance is also working on partnerships with Yiddish programs at nearby universities.

“The University of Michigan also offers Yiddish, and I’d love to have a friendly rivalry between our first-year Yiddish classes next year,” she said.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Free Love Unrequited: Translating a Yiddish #MeToo Narrative

4 p.m. March 19 at Page Hall 010

Jessica Kirzane, a Yiddish lecturer at the University of Chicago and editor in chief of In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies, will talk about her translation of Miriam Karpilove's Diary of a Lonely Girl. From the perch of a diarist writing in first person about her own love life, Karpilove's Yiddish novel of immigrant life told from the perspective of a woman offers a raw personal criticism of radical leftist immigrant youth culture in early 20th-century New York. This event is part of the Translation and Interpretation Workshop Lecture Series and is co-sponsored by the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and the Melton Center for Jewish Studies.

Last Yiddish Heroes: Lost and Found of Soviet Jews during World War II

2 p.m. April 12 at the Columbus Jewish Community Center

Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter Psoy Korolenko and Yiddish scholar Anna Shternshis (University of Toronto) will present Yiddish songs of World War II as part of a new concert and lecture program. The event is co-sponsored by the Melton Center for Jewish Studies, Ohio State’s School of Music and supported by the Diane Cummins Community Education fund.

JOIN THE YIDDISH TISCH

Want to practice your Yiddish skills or learn more about Yiddish? Join Yiddish Tisch, a monthly club at the Schottenstein Chabad House at Ohio State.